Introduction

Hi everyone!

Today I want to explain why Markdown is a poor writing tool that you should avoid using in your documentation.

Markdown is the most renowned lightweight markup language on the Internet. It is used in readme documents, introduction guides, wiki pages, blog posts, comments. Its popularity is based on simplicity and low writing threshold. You can learn all the syntax in 60 seconds and start writing your first document with your favorite IDE almost in no time. This is especially good when composing quick notes to describe what the product does and basic usage commands. GitHub and GitLab even allow developers to automatically initiate new repositories with README.md file, though both projects support a multitude of languages, including Asciidoc and reStructuredText.

Let me guess your question - how can such a popular tool be so bad? Does it really have many drawbacks? In fact, there are more of them than you might imagine.

Why does Markdown fail?

I would like to outline the most annoying and frustrating limitations that may turn your experience when writing technical documentation with Markdown into a nightmare.

- Lack of specification. Since its launch in 2004, Markdown has had no technical specification except for that defined by John Gruber in his blog post. The absence of strong guidelines forced different projects to create their own rules of how Markdown should be parsed. As the result, the base Markdown syntax can have an extra set of features available only in a particular specification. For example, abbreviations or footnotes.

- Flavors. To mitigate the existing limitations due to the lack of specification, projects (especially static site generators) built on top of Markdown introduce new flavors with their own syntax. Currently, the list of flavors contains 34(!) entries. It is obvious that some of these flavors are incompatible with each other or even incomplete, so you have to keep in mind which flavor version you use to avoid syntax and build mistakes.

- Lack of Extensibility. Markdown doesn’t have an extension system that would allow you to extend the language without affecting the way it is parsed.

- Lack of Semantic Meaning. With Markdown you can only write text. It means that if you need to grab the reader’s attention with some kind of notes or tips, you have to embed HTML. The lack of semantic support is a problem for a few reasons:

- Markdown is now dependent on specific HTML classes, and page design

- Document content is no longer portable to other output formats

- Conversion to other markup tools and page designs becomes much harder

- Lock-In and Lack of Portability. The tons of flavors and the lack of semantic support results in a lock-in. The more documentation you have, the more you are tied to the existing configuration. After that, it is hard to migrate to another tool, as custom-defined HTML classes and flavor’s features won’t work outside the current set of tools and page designs.

Any alternatives?

Markdown has two serious competitors: reStructuredText (rST) and AsciiDoc. Both are very similar in syntax and have a stronger set of features than Markdown. And the most important - both are designed to create documentation. I was using these plain-text formats for some time and Asciidoc appeared to be more interesting to me. So, let’s give it a small overview.

Why does AsciiDoc succeed?

AsciiDoc is deprived of the shortcomings I mentioned above for Markdown. In addition, AsciiDoc has some killing features that don’t exist in Markdown, including:

Code Blocks

AsciiDoc allows you to add “live” code snippets directly from source files. With this kind of inclusion, you don’t have to worry about outdated examples in documentation as they will be updated automatically once the source code is changed. For example:

include::source_code.js []It is also possible to include a part of a source file using tag attribute. So, you place the section that should be included between these tags:

// tag::code_example[]

function multiply(num1,num2) {

var result = num1 * num2;

return result;

}

// end::code_example[]and then include this section using include directive:

include::source_code.js[tag=code_example]Attributes

Attributes are used to enable internal features or hold replacement content like variables. For example:

[options="header,footer,autowidth"]

|===

| Cell A | Cell B

|===The example above shows three defined attributes for a table. More details about tables I described here.

Another example:

:toc: right

:document_version: 1.1.0The first attribute displays Table of Contents on the right-hand side of the main content, whereas the second one includes a dynamic value of the document version within the content:

The current document version is {document_version}.In AsciiDoc, each element has its own set of attributes that allows you to flexibly configure this element. For example, with attributes for images you can add an alternative title, dimensions, external link, define floating and role. In Markdown, the only way to do the same is to use inline HTML.

Conditional directives

Attributes are the key to another cool AsciiDoc feature: conditional content inclusion. With special directives ifdef, ifndef, and ifeval you can control what content should be displayed depending on certain conditions are met.

Use ifdef directive to show content if the specified attribute is set:

ifdef::github[]

This content will be displayed for GitHub users only.

endif::[]Conversely, ifndef directive is used to hide content if the specified attribute is not set:

ifdef::github[]

This content will not be displayed for GitHub users.

endif::[]ifeval directive shows content if the expression inside the square brackets evaluates to true. This may be helpful to show instructions only for particular versions of documentation:

ifeval::[{api_version} < 2.0.0]

If you want to use API methods available in version {api_version}, use the following endpoint: `https://example.com/api/v1/

endif::[]Building Blocks

Building blocks are special components to include non-paragraph text, such as code listings, quotes, tables, etc. This gives you a greater flexibility in adding versatile content in your document.

For example, you can add a listing block like this:

----

This is an example of a _listing block_.

The content inside is displayed as <pre> text.

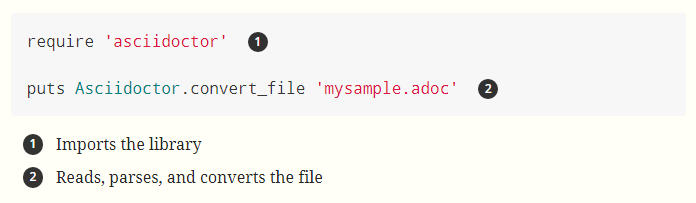

----or like this by adding callouts for additional information right in the sample:

[source,ruby]

----

require 'asciidoctor' # <1>

Asciidoctor.convert_file 'mysample.adoc' # <2>

----

<1> Imports the library

<2> Reads, parses, and converts the file

Another powerful block is an open block. It can act as any other block and contain any information you want. This may be useful as a non-intrusive way of including content. For example:

[sidebar]

.Related information

--

This is aside text.

It is used to present information related to the main content.

--Admonitions

AsciiDoc supports 5 types of admonitions out-of-the-box: Note, Tip, Important, Caution, Warning. The great thing here is that admonition can also encapsulate any block content. If you remember, in Markdown admonitions are some sort of blockquotes and writing a section that includes examples with special formatting is a total disappointment. In AsciiDoc, you just add the desired content with the selected type of the admonition.

IDs, anchors, and classes

In Markdown (I mean, base syntax), the only thing you can do is to override the auto-generated heading anchor with your own user-friendly slug. With AsciiDoc, you can add a custom anchor almost anywhere: on a section title or discrete heading, on a paragraph, on a block, on a link or inline image, on listing or literal block, on a phrase, and so forth.

For example:

ID for a paragraph

[[notice]]

This paragraph gets a lot of attention.

or

[#notice]

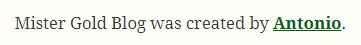

This paragraph gets a lot of attention.Furthermore, classes and additional attributes are available for links. The base syntax looks as follows:

link:url[optional link text, optional target attribute, optional role attribute]So, you can write something like that:

Mister Gold Blog was created by https://mister-gold.pro/[*Antonio*^, role="green"].and receive a link with bold green text that will be opened in a new tab. Again, these manipulations are possible with no hints of inline HTML or hardcoded CSS classes in it.

Tables

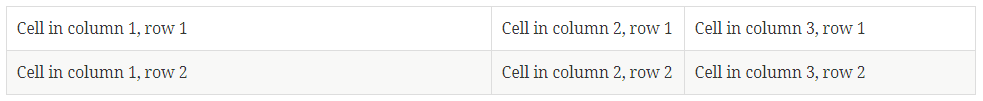

Tables are available in Markdown as well. But what can you do with them? Align content… aaaand… that’s it. Asciidoc provides a variety of ways to control the size, style, and layout of content within columns. Span over columns and rows, add nested tables, duplicate content across columns, and even display table in landscape mode - I bet this is the best experience with table formatting you ever had.

Some examples:

Different table width

[cols="50,20,30"]

|===

|Cell in column 1, row 1

|Cell in column 2, row 1

|Cell in column 3, row 1

|Cell in column 1, row 2

|Cell in column 2, row 2

|Cell in column 3, row 2

|===

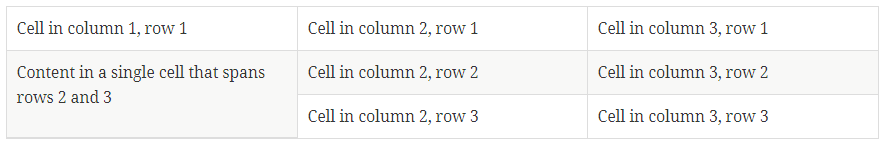

Spanned rows

|===

|Cell in column 1, row 1 |Cell in column 2, row 1 |Cell in column 3, row 1

.2+|Content in a single cell that spans rows 2 and 3

|Cell in column 2, row 2

|Cell in column 3, row 2

|Cell in column 2, row 3

|Cell in column 3, row 3

|===

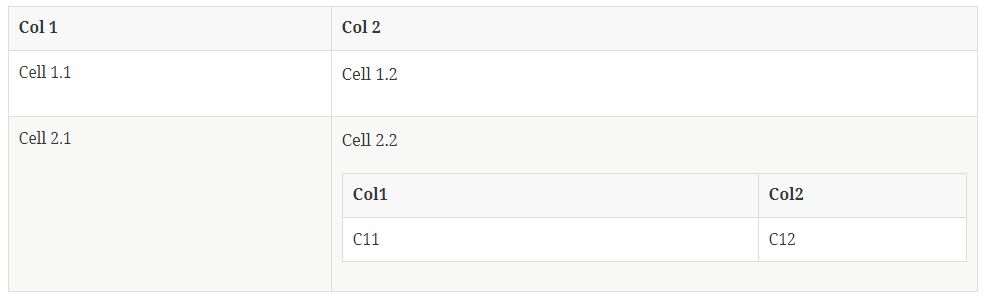

Nested table

[cols="1,2a"]

|===

| Col 1 | Col 2

| Cell 1.1

| Cell 1.2

| Cell 2.1

| Cell 2.2

[cols="2,1"]

!===

! Col1 ! Col2

! C11

! C12

!===

|===

Other

Besides the joker features that stand out, AsciiDoc also has lots of syntax “tricks” that make documents more consistent. I will not dive into too many details here, just list some of them:

- hard breaks: you no longer need to insert blank lines to separate two paragraphs or pieces of content. Just add a plus sign at the end of the line and you’re done!

- list continuation: add a descriptive paragraph or a building block directly to the parent or child list items.

- block titles: a small visual enhancement that makes content more readable.

- lists: with the help of built-in attributes you can make interesting modifications, like defining the starting number, creating a list with reversed numbering, or even a list with command listing without any text.

- math equations and formulas: to insert a math equation of any complexity, just set the

stemattribute in the document’s header.

These tricks are almost unlimited - you will find more cool aspects, as you learn AsciiDoc better.

Conclusion

Actually, I was surprised by the fact that so many people think Markdown is a really powerful tool for documentation. Especially, considering the number of articles with the similar topic that appear on Medium. The premises for all these stories are almost identical. You start with a simple document or a set of documents. At this point, the instinct to choose Markdown is good. The fast learning curve and primitive syntax seem to be a winning combination. However, as your documentation evolves and you need something more complex, Markdown simplicity becomes the greatest shortcoming. Ultimately, you end up using flavors (to overcome native limitations) that wreck portability or searching for better alternatives.

It reminded me of two interesting blog posts that I found some time ago. In the first one, Eric Holscher (the co-founder of Read the Docs and Write the Docs) told why you shouldn’t use Markdown for documentation. His article looked convincing, as I tend to trust the opinion of a person who has arguments against Markdown, while he is working on a product that supports both Markdown and reStructuredText. In the second article, Tom Christie tried to refute Eric’s arguments. But his arguments were rather controversial as Tom described only his cases to use Markdown. The answer why Tom was sticking to Markdown was clear - his project is large (hosted with MkDocs), but has nothing more than code blocks under the hood. Markdown is good enough here, for sure.

As I said before, Markdown has lots of limitations out-of-the-box that cannot be resolved based on the existing CommonMark specifications. For example, sections reusage, source code inclusion or dynamic variables. As the result, Markdown fits only for creating basic documents like READMEs or simple knowledge bases.

AsciiDoc, in turn, offers better semantic richness, standardization, and support of multiple output formats (HTML, DocBook, PDF, and ePub). It also supports a broader range of syntax than Markdown, so the main focus was set on ensuring the maximum reusability of the content, whereas the syntax was designed to be extended as a core feature. This truly makes AsciiDoc the right investment as a complete, all-sufficient tool for creating documentation of any size, including auto-generated API docs.

And finally…

According to John Gruber, the inventor of Markdown:

Markdown’s syntax is intended for one purpose: to be used as a format for writing for the web.

So, I want to finish this article with the simplest conclusion ever:

Do not use Markdown for things it was not designed to do. For example, to write documentation.